Hunger Report

2023Insights on Food Insecurity and Inequity in the Greater Washington Region

Foreword

In several regards, the past year has been far closer to what many would consider “normal” than any time since early 2020. The last 12 months have been marked by significantly fewer of the sudden COVID-related disruptions, closures, and restrictions that characterized earlier phases of the pandemic, and in May of this year, the national pandemic emergency officially ended. High-level economic indicators, too, are currently looking much improved from years prior.

With these transitions back towards pre-COVID norms, it would be logical to assume that food and financial insecurity had stabilized and improved as well. But on the ground in our communities, the numbers tell a very different story. The Capital Area Food Bank (CAFB)’s network of nonprofit partners have continued to see more individuals coming to their doors, and our food distribution has remained significantly elevated. Last calendar year, the CAFB distributed the food for 53 million meals – 77% more than the same period in 2019.

To better understand the divide between these simultaneous narratives – one of recovery and normalization, and the other of continued economic instability – the food bank once again partnered with trusted independent social research organization NORC at the University of Chicago to conduct a general population survey about food insecurity and inequity in the region. General population surveys are the most reliable and accurate tools available for understanding the prevalence of key concerns and opinions in the context of broader society.

The results from this research, collected from nearly 5,300 residents and published here in our fourth Hunger Report, made unavoidably clear that while many things have improved over the last year, they have not improved equally for all people. This is perhaps most evident in rates of food insecurity, which, shockingly, are nearly identical to the prior year’s levels.

The survey data contained in Hunger Report 2023 reveal the multiple, often compounding factors that have driven food insecurity to remain at staggeringly high levels across the region. Many who were hit hardest by the impacts of COVID-19 have continued to be weighed down by several forces, including slow, inequitable economic recovery from the pandemic; near-record levels of inflation on everything from housing to fuel to food; and the end of many novel or enhanced federal benefit programs that had been keeping thousands of families and individuals afloat financially.

Cumulatively, all of these forces made it just as difficult for families to put food on the table this past year as it had been the year prior. Many respondents shared that their financial outlook was the same as, or even worse than, it had been a year ago.

The results of this year’s report again highlight many of the known correlations between food insecurity, race, educational attainment, and geography in our region, underscoring the impact of longstanding systemic racism and structural inequities.

Beyond exploring the key drivers of food insecurity, the results of this year’s report again highlight many of the known correlations between food insecurity, race, educational attainment, and geography in our region, underscoring the impact of longstanding systemic racism and structural inequities. The report also contains new data on the detrimental effects that a lack of access to adequate nutrition is having on the health of our neighbors, showing that the rate of those who experience diet-related illnesses that impact their daily lives is more than twice as high among those who are food insecure as it is among those who are not.

Finally, as with previous reports, we have drawn upon both survey findings and insights from the people we serve to provide a set of recommendations for the path forward. These include actions that every sector can take, ranging from immediate to long-term, to address the food insecurity and economic instability that continue to dramatically impact people in our region.

As the data make clear, the socioeconomic disparities in our community continue to deepen. Only our collective commitment to addressing these problems will stop this already profound gap from widening further and allow more of our neighbors to move towards greater stability and well-being.

Key Terms

DMV (or Greater Washington Area)

The DMV, short for DC-Maryland-Virginia, refers to the Washington, DC metropolitan area and includes the following jurisdictions: the District of Columbia; Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties in MD; Fairfax, Arlington, and Prince William Counties in VA; and Alexandria City, VA. (Within Fairfax County are included Fairfax City and Falls Church City. Within Prince William County are included Manassas City and Manassas Park City.)

Food Insecurity

Food insecurity, as defined by the USDA, is “a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life.” Individuals who are referred to as food insecure in the report were identified, using the USDA’s standard eighteen-question screener, as having experienced one or more food-related hardships at any point during the past year. The screener is used to identify four levels of food security: food secure, marginally food secure, low food secure, and very low food secure. In this report, the first two categories are referred to as food secure, and the third and fourth categories are referred to as food insecure. The fourth category is referred to as severely food insecure.

Hunger

Hunger is a physical symptom of a lack of adequate food. It is not a quantifiable term, but rather a description of the result that reducing one’s food intake can have. Hunger and food insecurity are not synonymous, though they are closely related.

Inequity

For the purposes of this report, inequity refers to an uneven distribution of resources or opportunity relative to need. Unlike “inequality,” which assumes all people should receive equal shares of support from the systems around them, the term “inequity” assumes that systems should work in favor of those starting with lower resources and opportunity, not against them.

Social determinants of health

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks. Categories of SDOH include economic stability, education, health care, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context.

Food Insecurity Trends in Greater Washington

Food insecurity across our region

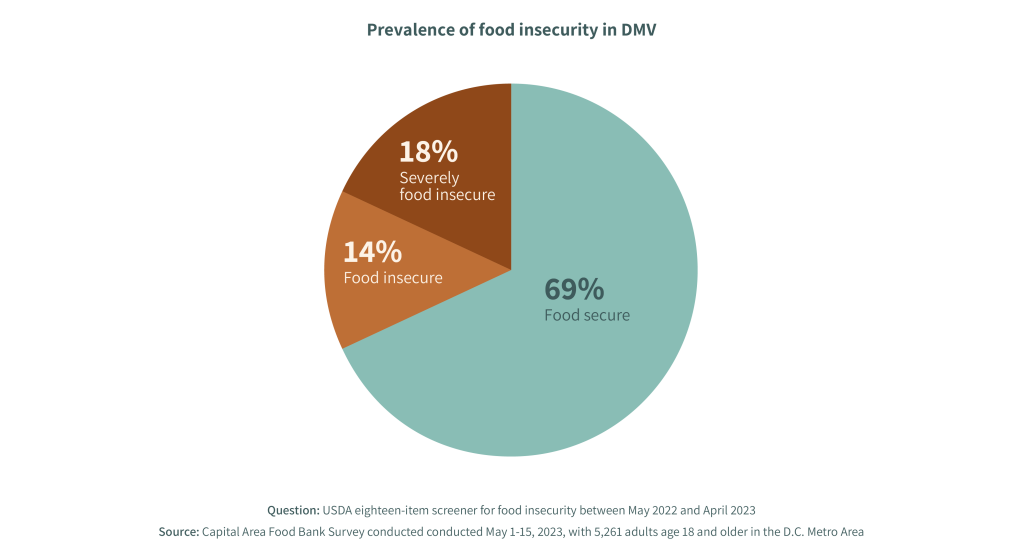

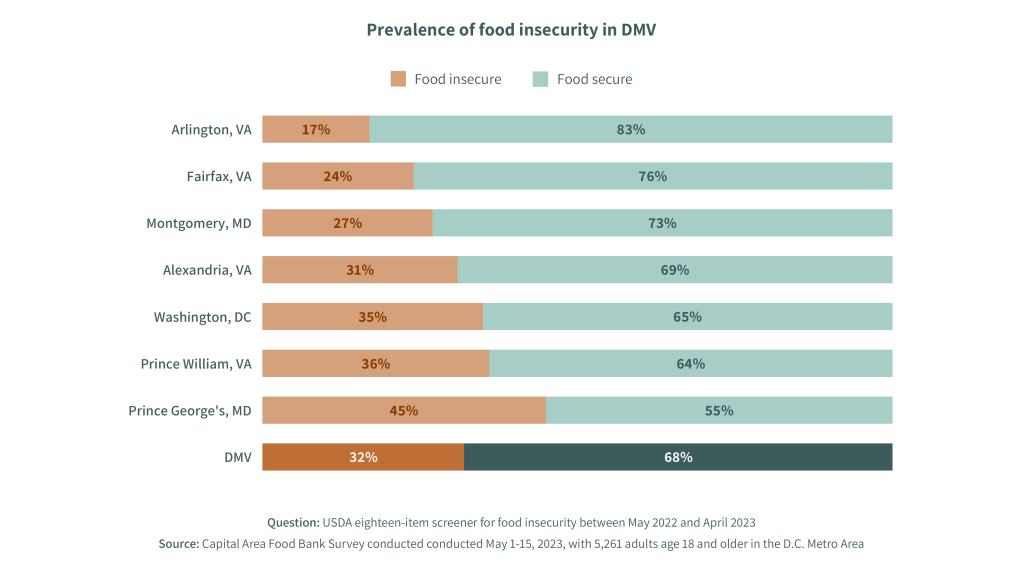

Given the mix of forces influencing household finances over the last year – including protracted impacts from the pandemic, inflation, and the wind-down of pandemic response programs from the government – the overall rate of food insecurity in the region has barely budged since 2022. In 2023, the Capital Area Food Bank’s study found that 32% of the region’s population experienced food insecurity at some point between May 2022 and April 2023, compared with 33% the year prior. Among these individuals, 14% are experiencing low food security and 18% are experiencing very low food security, as defined by the standard USDA screener.

Looking at food insecurity rates by county, the issue remains most severe in Prince George’s County, Maryland, where nearly one in two households experienced food insecurity at some point in the last year. Other areas where food insecurity rates are higher than the regional average include Prince William County in Virginia and the District of Columbia.

Insights on who is experiencing food insecurity

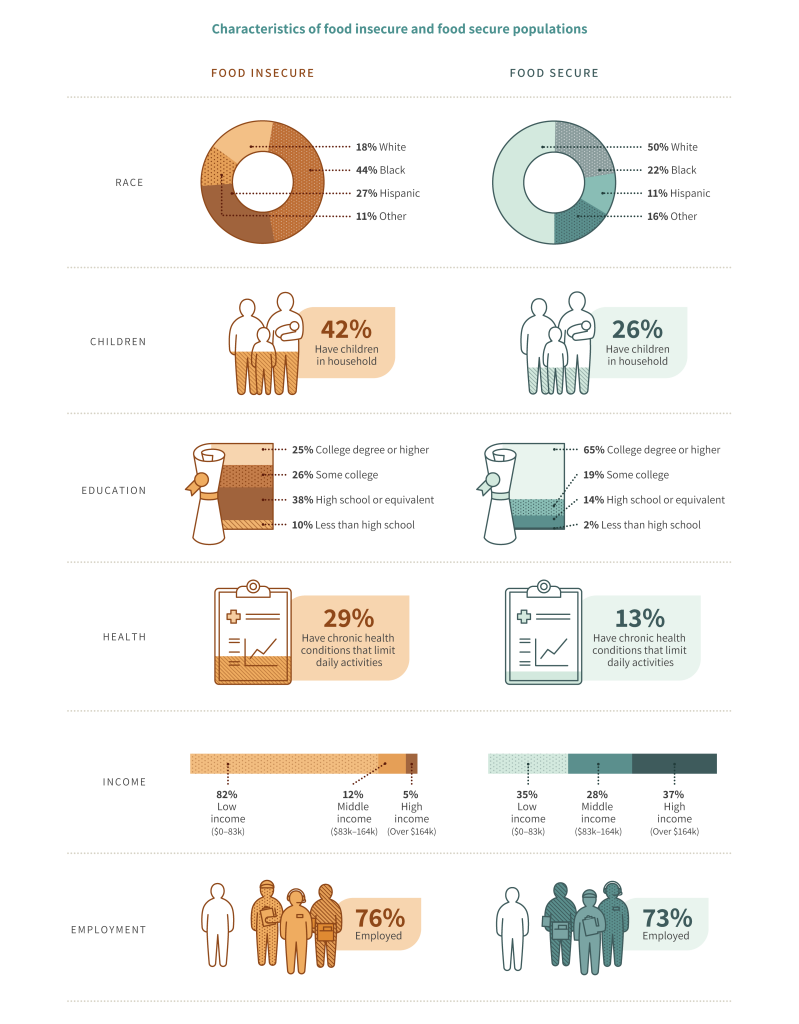

As in its 2022 study, the Capital Area Food Bank analyzed the socioeconomic characteristics of the population experiencing food insecurity to gain a better understanding of which groups are most vulnerable. By and large, the trends remain consistent: food insecurity disproportionately impacts people of color, households with children, and those with lower educational attainment and incomes.

Race

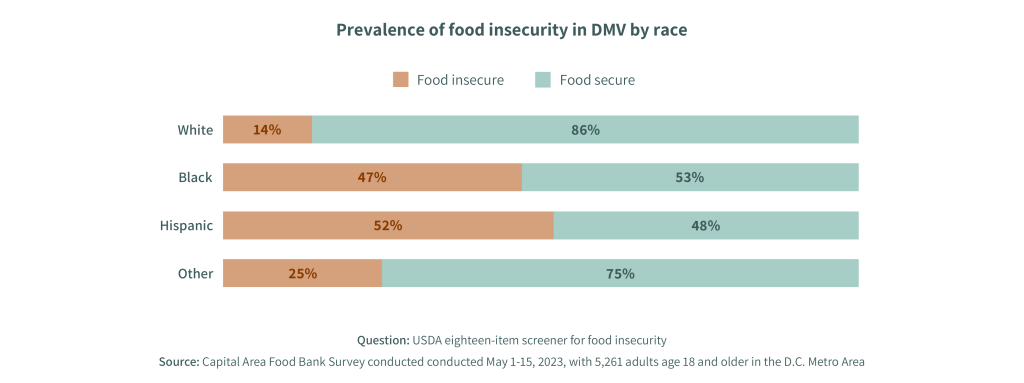

The Capital Area Food Bank’s 2023 study revealed highly disproportionate rates of food insecurity among Black and Hispanic respondents, a finding consistent with 2022’s data.Within the food insecure population, 44% of individuals were Black, and 27% were Hispanic, while only 18% were white.

Among the general population, approximately half of Black and Hispanic respondents screened as food insecure (47% and 52% respectively), compared to only 14% of White respondents. As noted in previous Hunger Reports, in observing the correlation between race and food insecurity, we must directly acknowledge the roles that systemic and structural racism—both historical and in present-day systems—play as drivers of the inequity in our region.

Children

The Capital Area Food Bank’s 2023 study delved deeper than in previous years into the dynamics of child food insecurity. The 2023 study found that, most of the time, in food insecure households with children, the adults screened as food insecure but the children themselves did not; this suggests that adults prioritize feeding the children first and – at least some of the time – are sacrificing their own food to do so. Indeed, child food insecurity rates are lower than general population rates, in part for this reason. Another key factor influencing this lower rate was universal access to free meals in public schools regardless of income, which ended in September 2022.

Across the region, the study found that 10% of children are experiencing food insecurity, compared to 32% of the general population. Food insecurity in children is a major concern given the established linkages between early childhood experiences of food insecurity and a range of poor health outcomes, altered development of the brain and central nervous system, diminished academic performance, and anxiety.

Heather’s family has struggled to access enough nutritious food, and her children are painfully aware of those struggles. One child has skipped meals intentionally, knowing that there isn’t enough to eat.

Health

There is a robust and growing body of peer-reviewed research that documents the negative health impacts associated with hunger and food insecurity, and the food bank’s 2023 study reinforces these connections. Nearly half of the region’s food insecure population is experiencing at least one diet-related health condition, including diabetes, high blood pressure or hypertension, or obesity.

Moreover, individuals experiencing food insecurity are more than twice as likely to report having a chronic health condition that limits their daily activities compared to their food secure counterparts (29% vs. 13%). These statistics underscore the need for interventions that address health and food insecurity simultaneously as interrelated issues.

Individuals experiencing food insecurity are more than twice as likely to report having a chronic health condition that limits their daily activities compared to their food secure counterparts.

Education

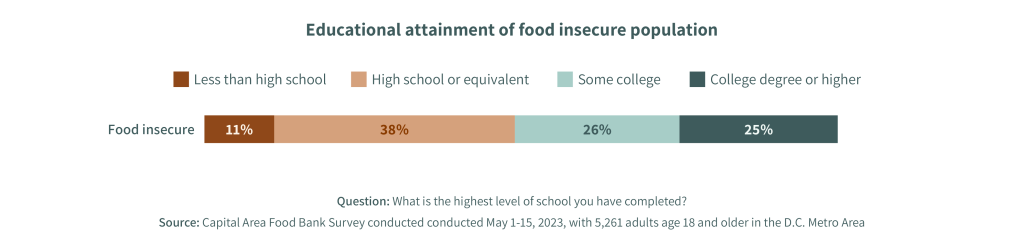

Over half of the food insecure population in Greater Washington has attained more than a high school diploma. Of these, half of them have completed some higher education – an associate’s degree or similar – and half are four-year college graduates.

This statistic underscores the need for greater equity in hiring, as well as increased access to degrees and certifications that align with post-pandemic job opportunities in the region.

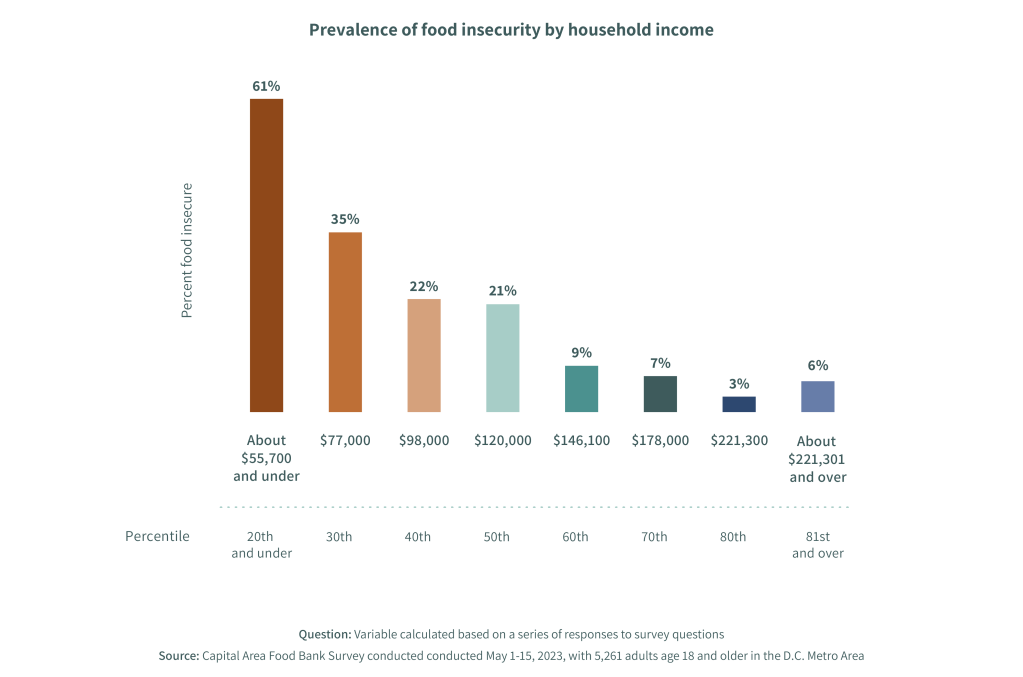

Income

Food insecurity is not concentrated under the poverty line. To the contrary, 67% of food insecure households earn more than the federal poverty wage. In fact, in a region with a cost of living as high as Greater Washington’s, it is not uncommon for households with earnings that put them well into the middle class to experience financial strains. The 2023 study found that even among households making $120,000 – the median for the region – food insecurity is affecting one in five families.

These rates of hardship among what should be considered middle-class families are not surprising when considering the median household income in Greater Washington, which is barely higher than the minimum cost of living in the area. According to the latest report from the United Way, a Household Survival Budget for a family of four in the National Capital Area in 2021 was $101,281. Similarly, the MIT Living Wage Calculator estimates that a family of four in the Washington DC Metro Area needs $124,345 to cover the costs of their family’s basic needs where they live.

Employment

As noted in the 2022 Hunger Report, employment rates are essentially equal between food insecure and food secure individuals: 76% of people facing food insecurity were employed, compared to 73% of those who did not experience food insecurity. (Both of these rates decreased by one point compared to 2022.) These high rates of employment suggest that the types of jobs that food insecure individuals have are simply not enabling them to make ends meet.

Odessa works multiple jobs, but she routinely faces weeks when she is not receiving a paycheck. At those times, she’s had to rely on assistance from food pantries to ensure she can bridge the gap.

Summary

Looking at these characteristics in concert, the profile of the most common households struggling with food insecurity are families of color who work hard – and earn up to a moderate income – but are still not able to make ends meet. These findings align with statistics on the population categorized by the United Way with the acronym ALICE: Asset-Limited, Income-Constrained, and Employed. In their 2023 report, the United Way of the National Capital Area found that the same proportion of the region’s food insecure population – one-third – also screened into the category of ALICE, reinforcing the overlap between these populations.

Key Drivers of Trends

Given the official end of the pandemic this past May and an overall economic picture that appears to have improved significantly over the last year, it may be surprising to many people that rates of food insecurity have remained virtually unchanged in our region. But those economic gains have not reached everyone equally, and multiple factors have continued to make it difficult for over a million people in the region to put food on the table consistently.

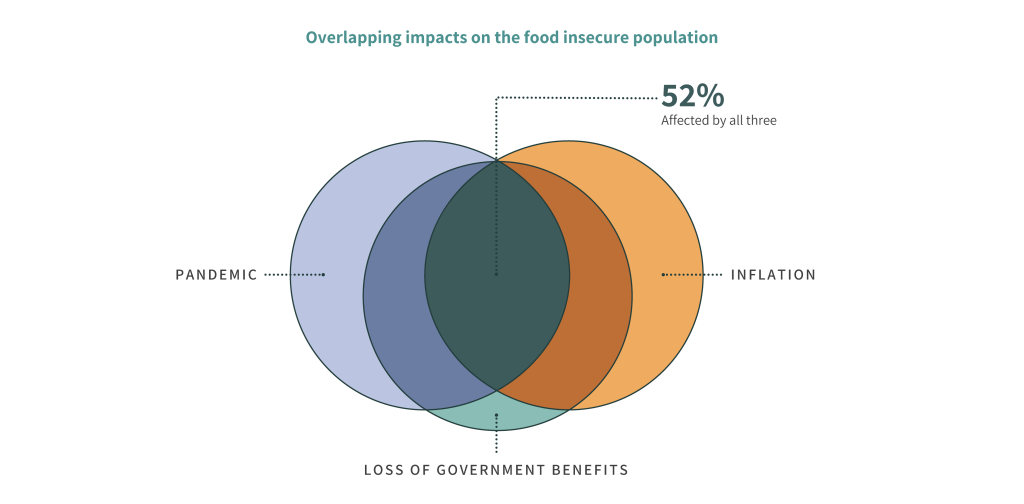

This year’s survey results show that the major drivers of food insecurity among residents of our region included the pandemic's ongoing impacts on employment, high rates of inflation, and the rollback of pandemic government assistance programs. Any one of these forces could cause difficult financial trade-offs for low-income individuals and families without any margin in their household budget, but many people experienced two or more of them simultaneously. And among those facing food insecurity, over half reported major impacts from all three of these dynamics.

The major drivers of food insecurity among residents of our region included the ongoing impacts of the pandemic on employment, high rates of inflation, and the roll back of pandemic government assistance programs.

This mix of impacts could have the effect of offsetting or erasing economic improvements made in one area (e.g., getting re-hired) with losses from another (e.g., losing government benefits). For many people, the counteracting effects of these forces kept them in roughly the same difficult position: working hard but struggling to make ends meet.

Those experiencing the compounding impacts of all three factors faced financial circumstances that were worse last year than the year prior. Accordingly, the views of many individuals in our area about their prospects for financial recovery remain low as they continue to struggle with the everyday realities of securing enough food for themselves and their families.

Protracted impacts from the pandemic

Three-and-a-half years from its onset, it goes without saying that the coronavirus pandemic has caused major economic hardship for millions of families across the United States – hardships that fell largely along racial fault lines and disproportionately impacted low-income households and families with children. In Greater Washington, those trends were no different: the Capital Area Food Bank’s 2023 study found that people of color, households with children, and those earning less than the median income all reported much more severe impacts from the pandemic than their respective counterparts. Among households experiencing food insecurity, 77% reported that the pandemic worsened their household’s financial situation.

Unfortunately, while the last twelve months have seen many headlines about the end of the public health crisis, the effects of the pandemic are not waning for everyone. Over a third of overall respondents in the study reported that their household’s financial situation has worsened in the last year, and over half of food insecure respondents reported the same. Food insecure respondents were also more likely than their food secure counterparts to report employment impacts, including being laid off (25% vs. 7%), scheduled for reduced hours (32% vs. 10%), taking unpaid time off (26% vs. 16%), or having their salaries reduced (31% vs. 9%) in the previous 12 months.

The study also asked respondents to describe how their household finances have recovered from the pandemic and, if they haven’t, how long they expect it could take to recover fully. Of those who reported that their financial situation was made worse by the pandemic (49% overall), only 12% say their household has recovered financially. Furthermore, rates of recovery vary widely by race and income level: white households were twice as likely to report having already recovered compared to only non-white households (18% vs. 9%). Nearly a third of impacted high-income households report already having recovered, compared to just 7% of low-income households. Among food insecure respondents, only 3% report having recovered financially, and the majority (68%) say that recovery is more than a year off.

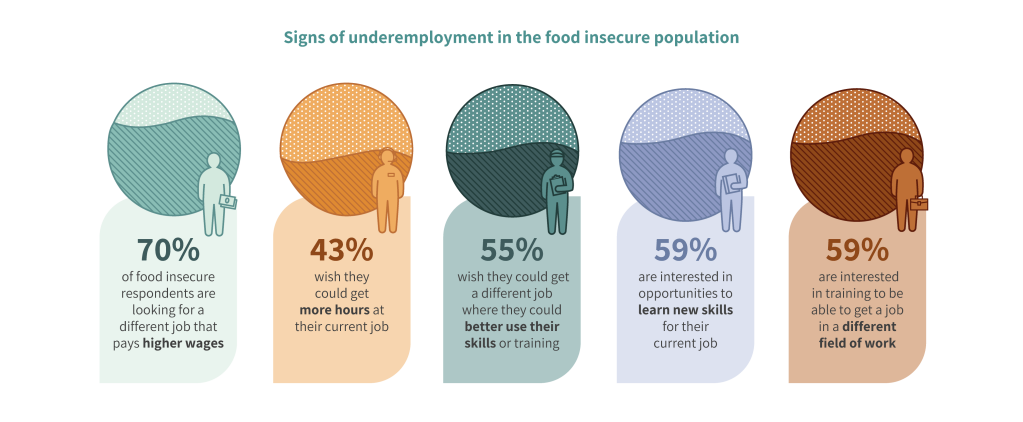

These bleak statistics stand in contrast to broader national reports of economic recovery. While unemployment numbers appear to have returned to pre-pandemic levels, even reaching historic lows, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations of these figures. For example, unemployment rates do not reflect full-time vs. part-time employment, underemployment, or if a worker has given up job-searching.

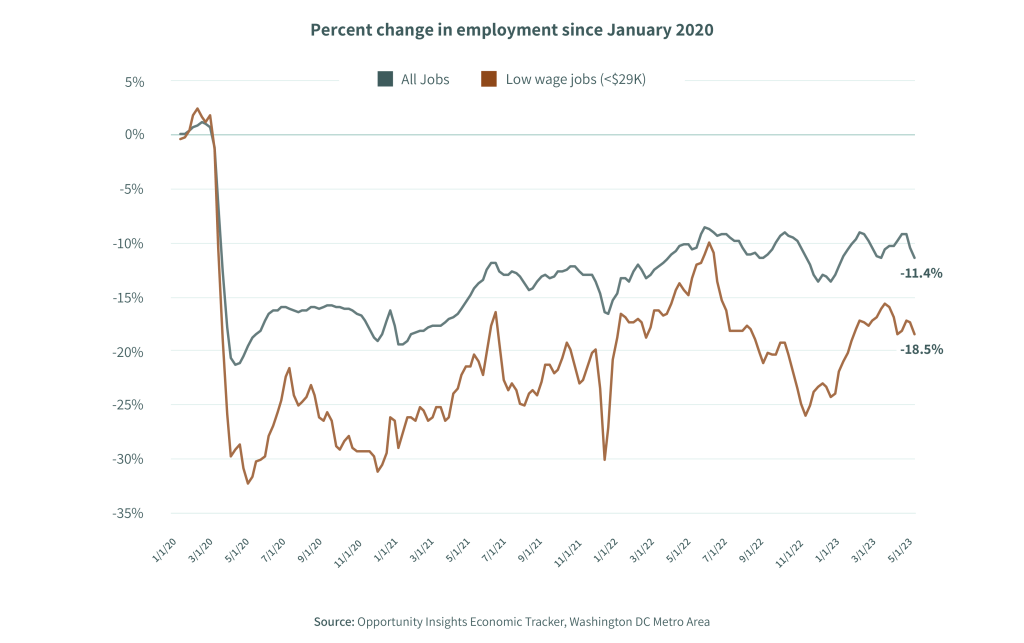

Employment is still 11.4% lower than it was in January 2020 and 18.5% lower for the region’s lowest earners.

In light of these limitations, looking at total employment rates for the Greater Washington metro area is more helpful for explaining sustained rates of economic hardship. Employment is still 11.4% lower than it was in January 2020 and 18.5% lower for the region’s lowest earners, based on data from Opportunity Insights. Contributing factors to these trends include lagging recovery of the leisure and hospitality industries, lower labor force participation rates, and wages that – while higher than before the pandemic – still do not offset the incremental costs of transportation and childcare that come with taking an additional job.

Even among those who are working, the quality of jobs is not necessarily high enough to cover the costs of living. Indeed, the food bank’s 2023 study found that, while the majority of food insecure individuals are working, most workers showed signs of underemployment and a desire for greater upward mobility.

Overall, these trends indicate that the majority of food insecure individuals experienced a protracted negative impact on their finances due to the pandemic and have still not recovered.

Rising costs due to inflation

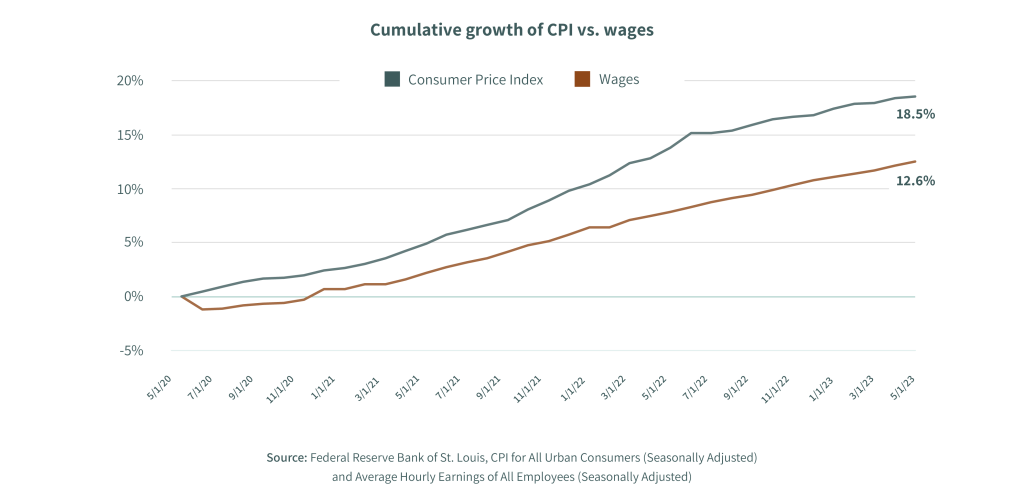

The pandemic’s impact on the global economy, along with ongoing global conflict, caused inflation to rise to some of the highest levels seen in over 40 years. Between May 2020 and May 2023, prices rose substantially across most spending categories. Overall, between May of 2020 and May of 2023, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose by 19%, meaning that an average of 19% more money is required today to purchase the same goods and services as three years ago.

When examining individual categories, many rates of inflation rates are even higher. The cost of food, for instance, rose 20%.

When examining individual categories, many inflation rates are even higher. The cost of food, for instance, rose 20%, and the costs of individual items that are staples for many people rose well above that above that, including milk (33%), canned mixed vegetables (36%), chicken (38%), and eggs (52%). This was also true for transportation: the overall cost of transportation rose by 31%, and the increase in average cost of fuel has been even higher (44%).

While the average cost of housing rose slightly less than the overall rate of inflation, it still increased by 17%. And the average rent in the DC metropolitan region has increased by over 15% since 2020, even for rent-stabilized housing.

Compared with these stark rates of growth in the CPI and other expenses, wages have not kept pace. Contrasted with a cumulative growth of 19% in the CPI from May 2020 to May 2023, wages have only increased 13%, leaving a significant gap between incomes and the rising cost of living.

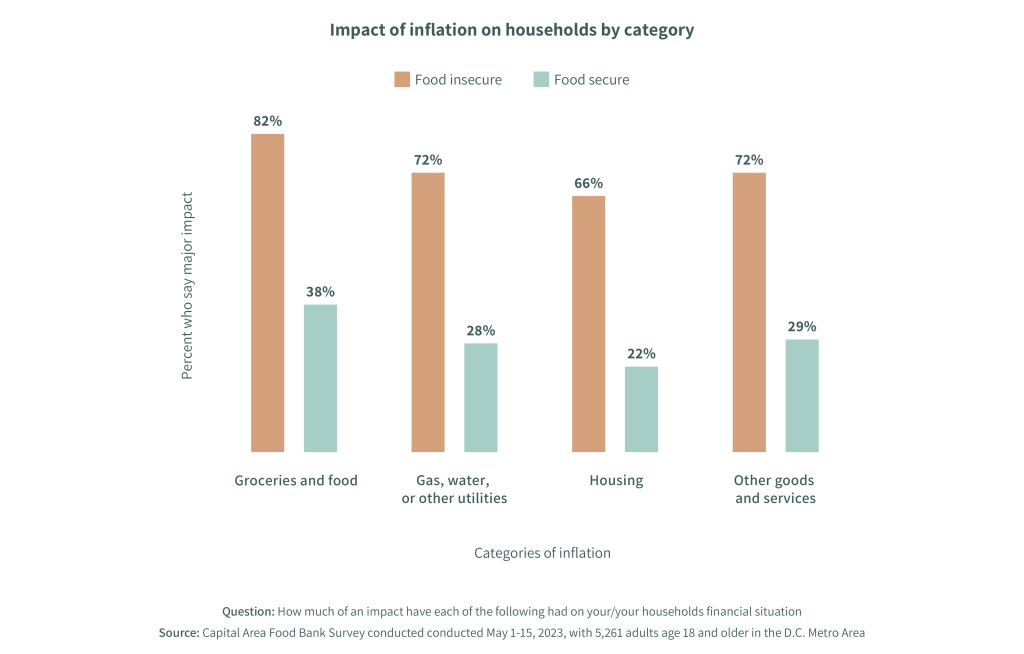

Unsurprisingly, the survey revealed that an overwhelming majority of adults said inflation or higher-than-usual prices for housing, food or groceries, utilities, and other goods had at least a minor impact on their financial situation. However, the effects of rising costs were felt most significantly by those whose budgets were stretched thin even before inflation skyrocketed: at least two-thirds of food insecure adults said inflation (or higher prices on each of the items asked about on the survey) had a major impact on their financial situation, compared to about a third or fewer food secure adults who say the same.

Those who reported the highest impacts of inflation on household finances were Black and Hispanic individuals who fell into the 30th income percentile and below, meaning their household income was less than $77,000. This racial disparity held true across all categories, including the cost of food. While higher-than-usual prices for groceries and food had a major impact on 52% of the population, that number increased to 66% and 67% for Black and Hispanic respondents respectively.

When inflation began to rise, Shawnte had to weigh the cost of driving to more affordable grocery stores against the potential savings for her food budget.

Sunsetting of pandemic government assistance programs

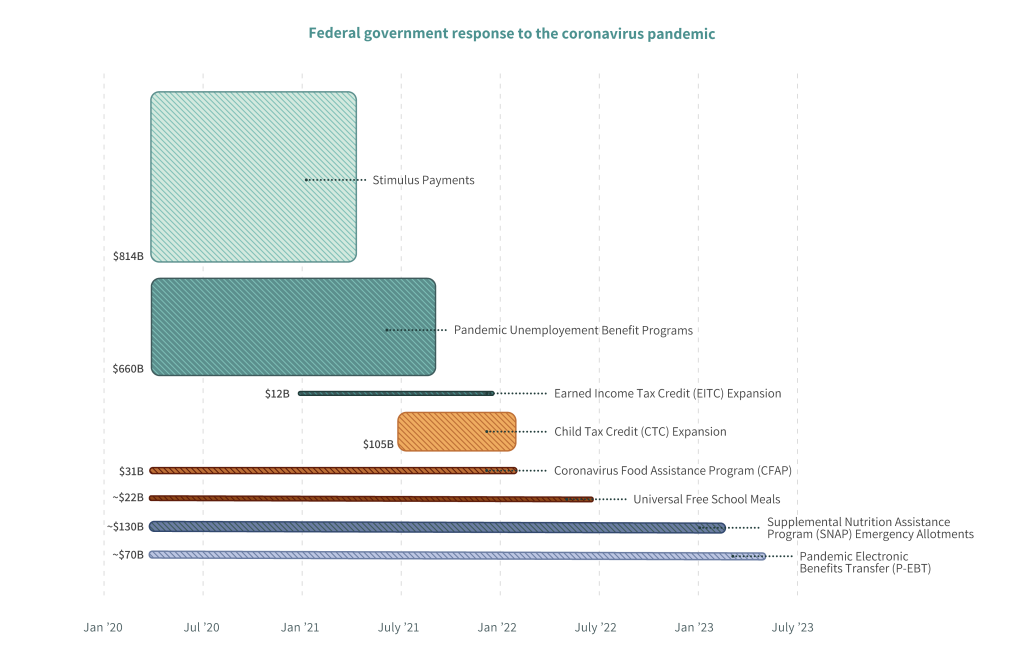

The pandemic caused profound economic turmoil, including widespread job loss and unemployment. To avert the worst impacts for the millions of people affected by these forces and to stabilize the economy, the US government temporarily enhanced the benefits available through several existing federal assistance programs and created multiple new ones. Over the course of several years, these programs included a wide-ranging set of supports.

During the pandemic, the federal government also allowed for many administrative flexibilities in how programs were able to operate and expanded eligibility criteria that extended program access to more people. Cumulatively, these programs and flexibilities have been widely shown across multiple studies and indicators to have prevented catastrophic suffering and in fact to have reduced poverty for millions of Americans.

One of the most significant program enhancements was the temporary increase of benefits to the SNAP program, on which 19% of those facing food insecurity in our region rely.

In the case of federal food assistance, one of the most significant program enhancements was the temporary increase of benefits to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistant Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps), on which 19% of those facing food insecurity in our region rely. In March 2020, benefit amounts for all SNAP recipients were raised to the maximum level allowable based on household size. These increases, known as Emergency Allotments (or EAs), meant that no recipient household was receiving less than $95 in benefits per month, and many families received substantially more. Particularly for households that had been receiving minimal levels of benefits prior to this increase, these enhancements offered a meaningful jump in support.

The survey results make clear the positive impacts of this increase on household budgets and food security for SNAP recipients in our region: 70% of SNAP recipients reported that the increase in benefits caused a major, positive impact on their household’s financial situation.

In March of 2023, however, pandemic-era SNAP Emergency Allotments wound down, causing a reduction in benefits for all recipients in the region. The average reduction in the greater Washington area was $93 per individual and $173 per household, though many people experienced even steeper declines.

In March, Shanita’s SNAP benefits decreased dramatically as food inflation was still soaring. As she attempted to stretch fewer dollars farther, she says she was no longer “eating for my health, but eating to survive.”

Just as increased SNAP benefits provided significant positive effects for recipients in the region, the rollback of EAs had substantial negative consequences for SNAP households. Seventy-five percent of SNAP recipients reported that the reductions to their benefits had a major negative impact on their finances.

75% of SNAP recipients reported that the reductions to their benefits had a major impact on their finances.

The end of these benefits came even as many of those surveyed are still recovering financially from the pandemic’s impacts. These reductions arrived alongside the wind-down of other pandemic-era programs, including the Child Tax Credit, extended unemployment support, and multiple other programs that had bolstered family finances during the past years of economic turbulence – leading to a cumulative adverse household impact.

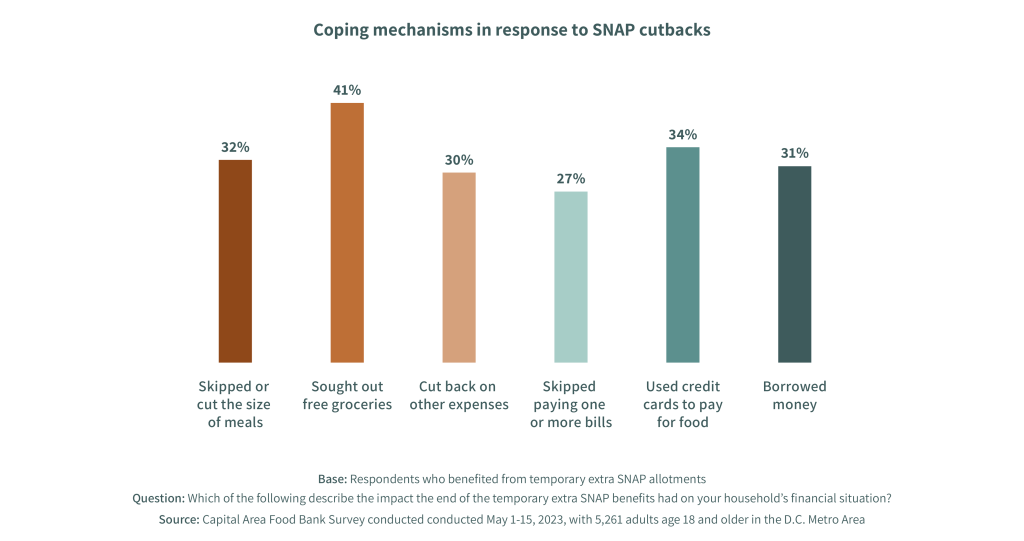

As a result, household finances – and food security – have suffered with the end of SNAP Emergency Allotments. The reduction of these benefits led to extreme coping mechanisms among one-third of recipients, including skipping meals, going to free food distributions, cutting back on other bills and expenses, using credit cards to pay for food, and/or borrowing to make ends meet.

Recommendations for Addressing Food Insecurity

The impacts of food insecurity and the forces that shape it extend broadly across our region and touch every sector. Strategies for addressing these problems, therefore, must be similarly far-reaching, complementary, and highly collaborative. The below section recommends several strategies for addressing food insecurity on a spectrum of short-term to long-term approaches. Some have been discussed in prior reports and are covered again here to underscore the consistency of the issues influencing food security and the importance of approaching this challenge holistically.

In effect, each of these strategies drives outcomes in the core issue underlying food insecurity: economic inequity. There are many initiatives already underway in our region in each of the below-examined categories that are enabling equitable economic recovery from the pandemic and supporting pathways to opportunity. These initiatives are worthy of recognition and should be developed further through increased investment from all regional stakeholders in economic equity.

Increase the accessibility of the emergency food assistance network

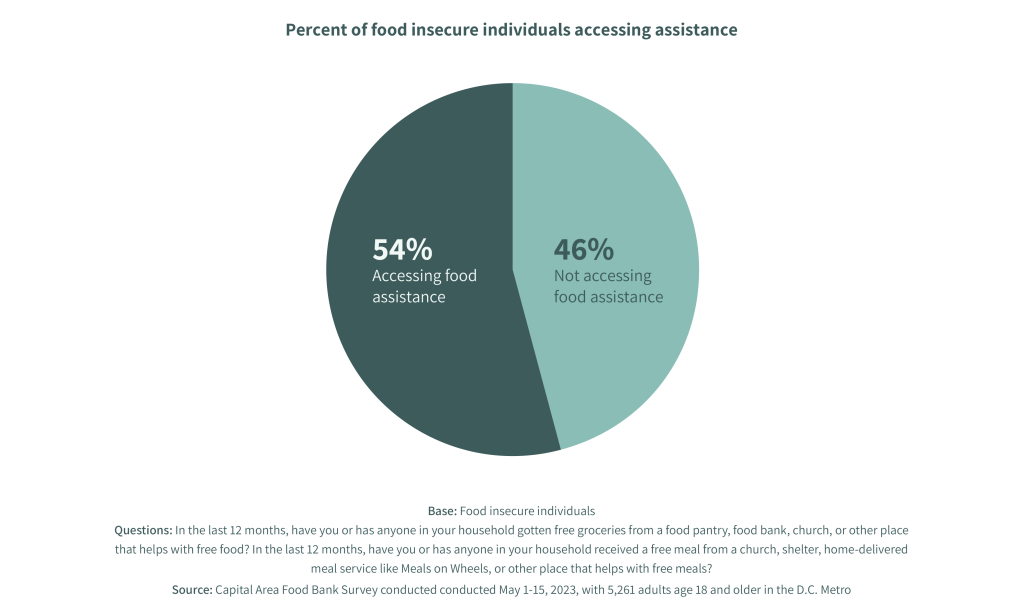

Among those who have experienced food insecurity in the last year, only 54% have gotten free groceries or meals from a food pantry, food bank, church, or other place that helps with free food. This means that roughly half of the food insecure population is not accessing the supports being offered to them by the charitable food assistance network, despite the ongoing efforts of hundreds of organizations across the region committed to addressing food insecurity.

These low rates of utilization, along with findings from other helpful studies on the accessibility of the food assistance network, suggest that there are barriers to accessing the food assistance being offered throughout the region. Some of these barriers include low awareness of services, limited alignment with the cultures of those experiencing food insecurity, limited or misaligned hours of operation, and stigma.

To address these barriers, leaders in the sector and individual food assistance providers should consider the following strategies for increasing their reach and impact with unserved clients.

Increase access to information about food assistance providers

The Capital Area Food Bank’s 2021 study found that the majority of its clients (59%) only knew of one location where they could access free food, suggesting a lack of awareness of the resources available to them in their communities.

As noted in the final set of recommendations below – integrating approaches to addressing poverty – the ideal solution to this issue is to establish information systems that enable clients to self-navigate and social service providers to make referrals across multiple different domains of support, including but not limited to food assistance. A key feature of these systems should be that they are user-friendly and low-barrier for clients and social service providers.

However, an essential prerequisite for such a system is an accurate and complete database of food assistance providers across the region with current contact information, hours of operation, eligibility requirements, and other key information for those seeking assistance. While several organizations are engaging in efforts to develop and maintain such a database, the decentralized nature of the food assistance network and the varied levels of capacity of each provider have made it difficult to achieve and maintain total coverage. To overcome these challenges, significant collaboration and investment from network conveners is needed.

Adapt languages and food types to the cultures of people seeking assistance

Compared to the food insecure population that currently accesses charitable food, the unserved population is just as likely to be non-English speaking, but it is more likely that the language they speak at home is a language other than Spanish. These individuals are often new Americans or resettled refugees and have less-established social support networks.

The diversity of this population underscores the need for food assistance providers to adapt their services to the cultures and ethnicities of the food insecure populations they serve.

The diversity of this population underscores the need for food assistance providers to adapt their services to the cultures and ethnicities of the food insecure populations they serve. This includes aligning the languages spoken by staff and volunteers, the types of food that are distributed, and other cultural norms with the ethnicities of their neighbors who are seeking support.

The Capital Area Food Bank has prioritized the cultural diversity of its clients through its food-sourcing strategies and is tracking the languages spoken at its network partner agencies in order to support services that create greater alignment with the diversity of the food insecure population.

Align hours of operation with the schedules of underserved neighbors

The food bank’s 2023 study found that food insecure individuals who are not receiving charitable food are more likely to be working than their counterparts (81% vs. 70%). Moreover, they are nearly three times as likely to be working over 40 hours per week (32% vs. 12%) and twice as likely to have more than one job (13% vs. 6%). This suggests that the unserved food insecure population has even less time available to spend obtaining free food and a lower likelihood that they will be free during most food pantries’ regular hours of operation.

One simple strategy for increasing the accessibility of the food assistance network for this population is for providers to offer realigned or additional hours of operation. Oftentimes, the schedules for food distributions are set based on the availability of volunteers and staff, but tailoring schedules to the availability of the clients served – ideally, based on data gathered from this population – would increase the reach of these programs and services into their communities. Additionally, it is common for food distributions to take place just once per month. When possible, more frequent distributions would reduce the need for food insecure clients to patch together food from multiple different food assistance providers.

Explore alternative service delivery models

Another strategy for addressing the limited and irregular times that these individuals have to obtain charitable food is to explore service-delivery models that do not require individuals to show up at a certain place at a certain time. Examples of these models include self-access food lockers and home delivery, both of which aim to eliminate the transportation and time barriers many experience to accessing the services of the food assistance network.

The Capital Area Food Bank has partnered with Door Dash to deliver thousands of food boxes directly to clients' homes.

These innovative delivery models are gaining traction in the social sector as food assistance organizations grow their partnerships with for-profit organizations like Amazon, Instacart, and Door Dash, leveraging existing infrastructure to meet the needs of food insecure individuals. The Capital Area Food Bank has partnered with Door Dash to deliver thousands of food boxes directly to clients’ homes and is exploring additional alternative distribution models and innovative partnerships with the private sector.

Acknowledge the importance of trust and stigma

A growing body of evidence has linked the experience of food insecurity with trauma. Besides the physical effects of inadequate nutrition, the overwhelming stress triggered by repeated and difficult economic trade-offs can cause long-term mental health issues, especially among children. This trauma from food insecurity, sometimes combined with additional traumas from other life experiences, must be acknowledged in the design for service delivery by food assistance providers in order for their support to feel accessible to clients.

To achieve this, food distributions should ideally be organized in familiar settings and run by known and trusted individuals. To the extent possible, staff and volunteers should be trained in trauma-informed care. The environment should feel welcoming and nonjudgmental, the physical space should be clean, and the food distribution process should include stress-free waiting and allow for client choice. Intersecting with the recommendation above on distribution models are food ordering systems that allow clients to select the foods they need and even have them delivered to a nearby location or their home. The combined effect of these adjustments to charitable food programs is to increase the accessibility of food assistance by reducing feelings of stigma and distrust.

Ensure the continued impact of highly effective government programs

By all measures, the levels of government investment and innovation directed to the social safety net and other support programs during the pandemic were some of the most significant in US history. That assistance, which included expansions in benefit eligibility criteria; higher benefit amounts; financial relief for individuals and businesses; and eviction and foreclosure moratoriums, among many other types, played a critical role in averting some of the direst economic impacts of COVID-19. According to some analyses, the number of people living below the poverty line would have risen by 8 million people in 2020 if not for government assistance.

As of May 2023, most all of those pandemic-era programs, enhancements, and flexibilities have now ended. With the number of struggling individuals and families in our region virtually unchanged since last year, the importance of maintaining and, where possible, strengthening remaining support programs has never been higher. The opportunity to do so is especially strong right now for the many federal nutrition programs funded through the Farm Bill: an expansive piece of legislation passed by Congress every five years that is up for reauthorization this year.

Strengthen SNAP

SNAP helps people in need put food on their tables by providing benefits to purchase groceries. As the largest federal program aimed at addressing food insecurity, the scale of the SNAP program as a front-line resource for those facing hunger is unmatched: for every one meal that a food bank like CAFB provides, SNAP provides nine.

The scale of the SNAP program as a front-line resource for those facing hunger is unmatched: for every one meal that a food bank provides, SNAP provides nine.

In our region, at least 328,000 people participate in this program. Its impacts on people’s budgets can be significant, especially, as discussed earlier in this report, when benefits are reduced to levels that do not adequately support a household’s current level of need. During Farm Bill reauthorization, there are many opportunities to ensure the future strength of the program by:

- Ensuring SNAP’s purchasing power remains strong so that benefits align with grocery prices and provide adequate support during challenging economic times. This will enable SNAP participants to access the nutrition they need while also freeing up funds that allow them to invest in other critical necessities like housing and health care. More broadly, it will also decrease the need for charitable food assistance, helping to reduce strain on food banks.

- Streamlining SNAP eligibility and enrollment to improve access for older adults, college students, immigrants, and low-wage workers. Current eligibility rules and enrollment processes are complex, can preclude those in need from participating, and do not reflect the nature of our modern student population and workforce.

- Better assisting individuals seeking employment. Congress can help SNAP participants find work by supporting effective state employment and training programs and ensuring people receive adequate SNAP benefits while job searching.

- Expanding the availability of culturally relevant foods in federal nutrition programs, such as halal-approved and -certified food and other items reflecting the diets of our diverse communities.

Strengthen income-based tax credits at the state level

Research has shown consistently that income-based tax credits are one of the most effective tools available for reducing poverty and food insecurity, increasing social mobility and significantly improving long-term outcomes on health, education, and even employment.

Two commonly claimed tax credits—the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC)—were both expanded at various levels of government during the pandemic. The impacts were dramatic. The 2021 single-year expansion of the Child Tax Credit, for instance, led to a historic reduction in poverty in the United States, especially among children. According to the US Census Bureau, child poverty fell to 5.2% in 2021, its lowest level on record.

While enhancements to the CTC and the EITC ended at the close of 2021, opportunity now exists for state governments to pick up where federal-level expansions left off. In our region, Maryland has recently moved in this direction by increasing the income limit for families to receive the child tax credit, and making all children under age 6 eligible. The state also made previous EITC expansions permanent; enabled people not claiming children on a tax return to receive the full credit value; and allowed non-citizen taxpayers to qualify. If adopted across other parts of our region, these policies have the potential to change the economic trajectory for thousands of additional people.

Streamline and strengthen TEFAP

The food that CAFB receives through government commodities, known as The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), has long been an important part of its overall donation stream. This has been especially true over the past several years, as spikes in food insecurity have been coupled with frequent supply chain disruptions. Having a consistent supply of nutritious foods to provide to clients is of paramount importance to all food banks, and TEFAP has played an important role in enabling that ability. Nationally, over 20% of the food distributed through food banks and local hunger relief programs comes from TEFAP.

Nationally, over 20% of the food distributed through food banks and local hunger relief programs comes from TEFAP.

With some program and policy adjustment, however, the reach and impact of TEFAP could be significantly increased, better allowing CAFB to meet the persistently high needs in our community. Such changes would benefit all food banks that distribute TEFAP.

Key ways in which the program could be streamlined or otherwise adjusted to provide a better experience for individuals receiving support, as well as for food banks administering the program and the distribution partners they work with, include:

- Reduce barriers to access for clients. Income eligibility thresholds create barriers to accessing TEFAP for individuals who are making too much to qualify for the program, yet struggle to make ends meet in areas with a very high cost of living. Lawmakers should remove or loosen these thresholds.

- Double the annual amount of funding for TEFAP entitlement commodities. The new level would ensure a steady flow of TEFAP foods to food programs like food banks and support the US agricultural economy.

- Provide sufficient funding to cover the program’s administrative costs. Lawmakers should create mechanisms to fund administrative costs, as well as other programmatic costs that do not currently cover the expenses associated with running the program.

- Diversify commodity food offerings. Policymakers should allow food banks greater autonomy over food selection, as the foods provided frequently don’t meet the cultural or health needs of the community members they serve.

The Emergency Food Assistance Program is an important and largely effective program, helping food banks maintain their supplies of food for those facing hunger. Addressing these priority areas will allow TEFAP to evolve and strengthen its capacity to help community members across our region and nation.

Accelerate Food Is Medicine interventions

Science has long shown that good nutrition is essential for growth, core body functions, and brain development. Increasingly, data also underscores that diet can drive the prevention, treatment, and even reversal of many illnesses, and there is a robust and growing body of peer-reviewed research that documents the negative health impacts associated with hunger and food insecurity.

Nearly half of the region’s food insecure individuals are experiencing at least one diet-related illness.

Those impacts are evident in the results of this year’s survey. Nearly half of the region’s food insecure individuals are experiencing at least one diet-related illness, and they are more than twice as likely to report having a chronic health condition that limits their daily activities compared to their food secure counterparts (29% vs. 13%) There exists a clear need to expand and accelerate the work being done to enable better health outcomes among this population.

At the intersection of efforts to create greater food security and those geared at enabling individuals to improve their health is a body of work known as Food Is Medicine (FIM). FIM encompasses a collection of programs and services that respond to the critical link between nutrition and chronic illness, and recognize healthful food as an important part of patient medical care and treatment. By advancing innovations, research, and ultimately, policies that allow these types of interventions to reach more people, the wide array of stakeholders engaged in FIM work have the opportunity to help millions of people, both in our region and nationwide, improve their health through access to nutritious food.

At the intersection of efforts to create greater food security and those geared at enabling individuals to improve their health is a body of work known as Food Is Medicine (FIM). FIM encompasses a collection of programs and services that respond to the critical link between nutrition and chronic illness, and recognize healthful food as an important part of patient medical care and treatment. By advancing innovations, research, and ultimately, policies that allow these types of interventions to reach more people, the wide array of stakeholders engaged in FIM work have the opportunity to help millions of people in our region and across the country improve their health through access to nutritious food.

Continue to pilot and expand innovative programs combining food and medical care.

Programs designed to address the health of food insecure individuals have proliferated in recent years, driven largely by nonprofit organizations serving populations deeply impacted by a lack of access to nutritious food.

Programs designed to address the health of food insecure individuals have proliferated in recent years, driven largely by nonprofit organizations serving populations deeply impacted by a lack of access to nutritious food. FIM programs use food as a medical intervention for diet-related illness and include multiple kinds of program models that fall primarily into the broad categories of medically tailored groceries, medically tailored meals, and produce prescriptions. In our region, there are multiple examples of this kind of programming, including those run by the food bank.

Programs focused on medically tailored groceries generally provide participants with a range of both perishable and nonperishable grocery items, including produce, that are supportive of their medical needs and sufficient to prepare nutritionally complete meals at home. The food bank currently operates multiple programs within this model through its Food Plus Health initiatives. By partnering with health care institutions to provide nutritious food directly at the point of care, these initiatives remove time and cost barriers for patients while helping to improve the results from their health services.

Among CAFB’s programming is an on-site food pharmacy program at Children’s National Hospital, which provides the families of food insecure children who have prediabetes, type 1 diabetes, or type 2 diabetes with shelf-stable groceries and fresh produce immediately following their medical appointments. Another program, known as "Healthy Mom, Healthy Baby," brings deliveries of fresh produce, shelf-stable groceries, and nutrition education materials to food-insecure pregnant patients diagnosed with diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, or obesity. Every two weeks during their pregnancy and for up to 12 weeks postpartum, participants receive fresh produce, protein, and whole grains, along with recipe cards and nutrition-education resources.

Medically tailored meals (MTMs), another type of FIM programming, are fully prepared meals designed by a registered dietitian to address an individual’s medical needs. In our region, CAFB food assistance partner Food & Friends provides home-delivery of MTMs and medical nutrition therapy to individuals living with cancer, HIV/AIDS, and other serious illnesses.

The third category of FIM interventions are known as produce prescription programs, through which medical professionals can prescribe fresh fruit and vegetables to food insecure patients diagnosed with a diet-related chronic illness. In the Greater Washington region, DC Greens’ produce prescription program provides eligible Medicaid recipients with monthly funds to purchase fresh fruits and vegetables at participating local grocery stores.

These kinds of programs, alongside many others, are increasingly shown to make a positive difference in the health of those who participate in them. Continuing to expand models with proven efficacy, and to pilot new interventions, will increase the availability of these programs for those who would benefit from them while also growing the pipeline of ideas to test, research, and potentially scale.

These kinds of programs, and many others, are increasingly shown to make a positive difference for the health of those who participate in them.

Grow the body of research exploring the efficacy of Food Is Medicine interventions.

An emerging body of evidence shows that Food Is Medicine programs have significant potential to improve health and quality of life for individuals across a range of health conditions, as well as to stem rising health care costs.

Medically tailored meals, for instance, are associated with improvements in health outcomes for HIV/AIDs, type 2 diabetes, heart failure, and chronic liver disease, as well as reduced health care utilization and spending for people who are seriously ill. Medically tailored groceries are associated with improvements in blood pressure and some type 2 diabetes-specific health outcomes. And research on produce prescription models, while just beginning to explore impacts on clinical health outcomes, demonstrates improvements in food security and dietary intake for a variety of participant populations.

Building on this promising early data and strengthening the case for FIM’s widespread integration into the health care system will require additional rigorous, high-quality research. Promising work is already happening on this front. When the Biden administration released its National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health in September of 2022, it named “enhancing nutrition and food security research” as among its five pillars. Shortly thereafter, The Rockefeller Foundation and the American Heart Association, along with the grocer Kroger, announced a plan to mobilize $250 million to build a national Food Is Medicine Research Initiative. The initiative’s stated goal is to “generate evidence and tools to help the health sector design and scale programs that increase access to nutritious food, improve both health and health equity, and reduce overall health care costs.”

Programs studied led to improvements in self-reported health status, fruit and vegetable intake, blood pressure, and blood sugar levels, as well as in rates of food security.

This investment is supporting some of the many new studies underway on the efficacy of FIM approaches, including research from Tufts University, Duke University, and the University of Texas that represents the largest collection of findings to date on the effectiveness of produce prescription programs and their positive physical and mental impacts on participants and communities. Programs studied led to improvements in self-reported health status, fruit and vegetable intake, blood pressure, and blood sugar levels, as well as in rates of food security.

The Capital Area Food Bank will itself soon be adding to this body of evidence by launching a research study in partnership with Children’s National Hospital that examines the efficacy of its medically tailored groceries program. By tracking 200 patients who receive food delivered weekly for a year, the study will measure the impact of program participation on attendance at clinical visits; increased consumption of healthy foods; and clinical outcomes such as blood sugar levels (A1c), body mass index (BMI), medication prescribed, missed medical visits, hospital readmission rates, emergency department visits, and behavioral outcomes, among others.

Creating a larger body of robust, high-quality, and purposeful research will equip the diverse stakeholders engaged in FIM work with the information they need both to build more effective programs and to advocate for the incorporation of these interventions as reimbursable parts of healthcare.

Enact policy changes that enable FIM programming to be covered as a reimbursable part of health care

While the positive impacts of FIM programs are evident, creating impact at a meaningful scale will ultimately require changing state and federal reimbursement structures to include FIM interventions as a covered benefit.

Currently, funding Food Is Medicine programming requires action at the state level. Multiple states, including Massachusetts, Oregon, North Carolina, and Arkansas are using a mechanism in Medicaid known as a section 1115 waiver that allows them to use federal funds to test programs that wouldn’t normally be included under Medicaid. Increasingly, states are using the waivers to fund programs that address what are often referred to as “social determinants of health,” a category that includes a range of non-clinical factors like safe housing, water pollution, and access to healthy, nutritious food.

While this mechanism has long been available to states, it has gained traction recently as the White House’s National Strategy directed the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) to issue guidance detailing how states can use waivers to test the expansion of food-as-medicine interventions. At the start of 2023, 23 states had such waivers approved or pending approval.

By pursuing these waivers for the purposes of funding innovative Food Is Medicine interventions, the governments of DC, MD, and VA can enable greater access to initiatives that are increasingly proven to help individuals improve their health, advance equity, and curb the cost of healthcare by reducing diet-related illness. Seeking 1115 waivers to pilot the support of FIM services would also contribute to the case for national adoption of FIM programs as covered Medicaid benefits.

Seeking 1115 waivers to pilot the support of FIM services would also contribute to the case for national adoption of FIM programs as covered Medicaid benefits.

To advance these aims in DC, the food bank and its partner organizations DC Greens and Food & Friends founded the DC Food As Medicine Coalition to fosters awareness around local FIM approaches and opportunities to scale them. That coalition has since grown significantly, with organization DC PACT currently coordinating efforts around a variety of services to recommend in a 1115 waiver.

Enable integrated approaches to addressing poverty

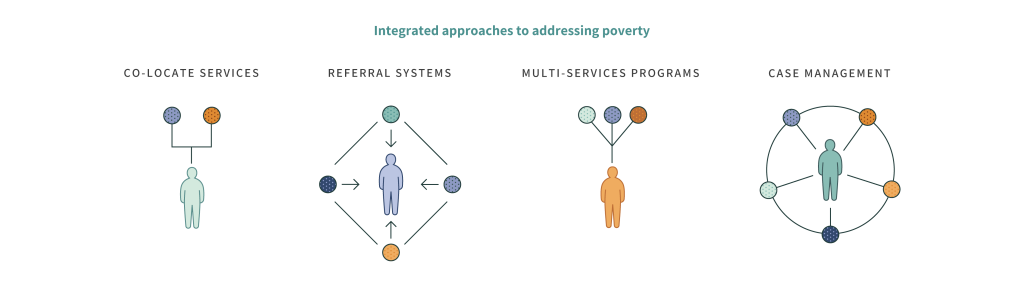

Barriers to prosperity are not singular for most people; they are numerous and interrelated, and they need to be addressed in tandem for interventions to be effective. A vast number of studies on social determinants of health have confirmed this, and in response, there is growing momentum around approaches to alleviating poverty that assume a continuity of care between different sources of support, including government, human services, healthcare, education, and other social sector actors. While achieving comprehensive coordination between all these actors is the goal, there are many intermediate strategies that can drive progress in this direction. Outlined below is a spectrum of approaches to address multiple barriers to prosperity, ranging from least to most fully integrated.

Co-locate services

At the most basic level, simple co-location services—that is, placing multiple resources in one location—can increase the accessibility of multiple forms of support by increasing awareness and removing the barriers of time and transportation needed to engage each one. This can look like offering health screenings at a food distribution site, for example, or a community center that operates a health clinic, a financial literacy center, and a food pantry in the same place.

Establish and strengthen referral systems

The next level of integration is to build and utilize comprehensive databases of social service providers to help facilitate connections between clients and as many forms of support as they wish to engage with. This can take the form of open-loop referral systems, which simply provide information on each service and rely on the client to access them individually, or closed-loop referral systems, which create warm handoffs between participating providers around individual clients. This latter form requires social service providers to use common information systems that can follow individuals as they are referred from one support to another and even track outcomes that signal success.

The next level of integration is to build and utilize comprehensive databases of social service providers to help facilitate connections between clients and as many forms of support as they wish to engage with.

In the Greater Washington area, several initiatives in this category are taking place. The Capital Area Food Bank has joined with the Federation of Virginia Food Banks to integrate a closed-loop approach through the adoption of the Unite Us platform across the Commonwealth of Virginia. In Washington DC, the Community Resource Information Exchange (CoRIE) is utilizing the CRISP Health Information Exchange platform to provide social support referrals for patients who screen positive for various needs.

Develop multi-service programs

The next level of service integration blends two or more different supports within the same program. Examples of this approach could include a job training program that includes a module on managing personal finances or a child nutrition program that includes nutrition education. This approach can be highly effective at magnifying positive outcomes for clients, especially when root challenges are interrelated.

The Capital Area Food Bank is employing this approach across numerous pilot programs, including its partnership with Northern Virginia Community College to support parenting students. In 2022, the community college - which already had a program established to support parenting students with federal funds to help cover childcare costs - partnered with CAFB to enhance those supports with increased access to healthy food through biweekly home deliveries of free groceries. The goal of the program is to remove multiple barriers to academic success for these students.

Promote case management style programs

At the far end of this spectrum is a fully integrated approach modeled after case management in the field of social work. In this approach, the client works with a provider to identify a range of needs, and the provider actively connects the client with each form of support, offering advocacy and accountability along the way to help overcome barriers presented by lengthy and complex administrative processes.

While this strategy is not novel, access to this kind of coordinated, long-term support is far from universal. Proponents of this approach – see the work of Transition to Success, for example – are increasing its accessibility by training non-governmental organizations in its methods, tracking results to prove outcomes, and advocating for investment in systems that enable coordinated care.

Conclusion

After years of disruption, daily life for many people has once again returned to a pre-pandemic level of normalcy. The economy seems, similarly, to have rebounded. Yet beneath the surface, the reality is far more complicated. The data are clear that better times have not come for everyone, and that for over a million people in our region who struggled to put food on the table in recent months, the economic picture continues to look uncertain.

These diverging narratives are indicative of the ever-deepening inequities that exist in our area, which have contributed to significant negative effects on the health, economic stability, and food security of people who were already vulnerable. Such impacts have consequences in the near term, but also threaten to create longer term hardships as well.

The enormous challenges of the last several years have created unprecedented visibility into the scope of the food insecurity and inequity that have been with us since long before COVID-19. With that visibility comes knowledge, and an imperative for change. There is an opportunity now for every sector to take steps that will not only prevent inequities from growing worse, but also create new pathways to financial stability and food security for a far greater number of our neighbors. While the pandemic is over, the urgent work of collectively addressing the longstanding problems it exposed must continue.