Hunger Report

2021

Insights on food insecurity, inequity, and economic

opportunity in the Greater Washington region

Foreword

The last year has been enormously disruptive for most of the globe. The COVID-19 pandemic—which had already been upending the U.S. for five months at the time of our last report—has now been with us for well over a year, and the world has continued to change rapidly during that time.

As more and more people have lost wages and faced dire economic circumstances, hunger and food insecurity have become significantly more prevalent and—even if temporarily—more visible. Food banks across the nation have seen historic highs in demand, with lines of cars snaking across miles of road while people wait for contactless pickup. The Capital Area Food Bank is no exception, having more than doubled the meals we provided—from 30 million to 75 million—to our neighbors in the nation’s capital region over the last year.

At the same time, events across the country have raised the consciousness of many Americans around issues of systemic racism and historical inequities. Public dialogue on these subjects has been more prevalent, frequent, and candid, and society has more readily acknowledged connections between these issues and a range of socioeconomic disparities, including those in food security rates.

Cumulatively, these events present a unique chance to examine the issue of food insecurity, its impacts across society, and its many contributing factors with a fresh lens. Particularly now, as the country is poised to resume more “normal” life in the coming weeks and months, we face an urgent opportunity to address both food insecurity and the broader inequities across our society in new ways.

With an eye toward the future, we have once again sought to pull together the available information for the Greater Washington community to gain a comprehensive, region-specific look at COVID-19’s immediate and longer-term impacts on vulnerable individuals and communities in our region over the last year.

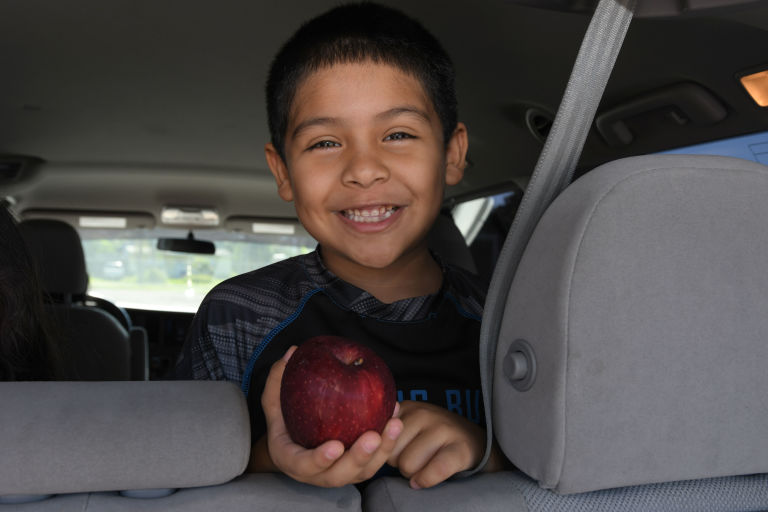

At the core of this year’s report are the recent results of a biannual survey of nearly 2,000 individuals from the communities we serve, which provide ground-level insights into the impact of the pandemic on our neighbors’ lives. The results of this survey form the basis for a series of observations on our clients’ greatest barriers to food security, their utilization of social services, and whether the pandemic was their first time experiencing food insecurity. While some of these findings were expected, others raised new questions about the driving forces behind food insecurity this past year and about future implications.

Our survey of nearly 2,000 individuals provides ground-level insights into the impact of the pandemic on our neighbors' lives.

Finally, we have devoted a significant portion of this report to exploring the roles that every sector—public, private, and nonprofit—can play in creating a regional economy that benefits more people by removing barriers to food security and creating greater opportunity for our neighbors. Based on what our clients have told us about the best pathways forward, we have identified several priorities for leaders in our region in pursuit of increasing food security and economic opportunity for all.

Key Terms

Food insecurity

Food insecurity, as defined by USDA, is “a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life.” Food security is measured through the Current Population Survey administered by the U.S. Census Bureau and has multiple levels of severity: high, marginal, low and very low.

Inequity

For the purposes of this report, inequity refers to an uneven distribution of resources or opportunity relative to need. Unlike “inequality,” which assumes all people should receive equal shares of support from the systems around them, the term “inequity” assumes that systems should work in favor of those starting with lower resources and opportunity, not against them.

Hunger

Hunger is a physical symptom of a lack of adequate food. It is not a quantifiable term, but rather a description of the result that reducing one’s food intake can have. Hunger and food insecurity are not synonymous, though they are closely related.

Quality employment

Quality employment opportunities offer a living wage, adequate paid leave, standard benefits including affordable health care, and opportunities for upward mobility.

Inclusive economic growth

Economic growth that is distributed fairly across society, increases economic opportunity and participation for all, and leads to shared prosperity.

Washington Metropolitan Area (or Greater Washington Area)

The Washington, DC metropolitan area, as used in this report, refers to the District of Columbia; Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties in Maryland; Fairfax, Arlington, and Prince William Counties in Virginia; and Alexandria City, Virginia. (Within Fairfax County are included Fairfax City and Falls Church City. Within Prince William County are included Manassas City and Manassas Park City.)

Food Insecurity and Other Inequities

Any discussion of food insecurity must come with the acknowledgement that this issue does not exist in a vacuum. It has many contributing factors and is most often an indicator of other individual and societal barriers.

At the root of most food insecurity is financial instability, along with its numerous related challenges—namely, the forced trade-offs between nutritious food and other necessities. Other common and interconnected issues include unemployment, low availability of affordable housing, disability status, social isolation, and transportation hurdles that make it difficult to travel to work or a distant grocery store.

Sometimes I have to choose food over my medicine and that’s not a good thing. The doctor wants me to take it every day. Trade-offs, we all have to make these trade-offs.

These challenges, too, do not exist in isolation. We must directly acknowledge the role that racism and oppression—both throughout history and in present-day structures—plays as a driver of the inequities that perpetuate these challenges and lead to their outsized impact on people of color. Longstanding and ongoing discriminatory practices in employment, housing, education, lending, municipal planning, and beyond continue to affect many communities of color.

As a result, access to opportunity in our country and in our region is far from equal. Many of our neighbors are earnestly seeking opportunities to thrive but are still held back by a web of interrelated forces that form barriers to progress.

Accordingly, current socioeconomic indicators for Greater Washington are highly disparate between racial groups. Even before the pandemic, indicators such as educational attainment, household income, net worth, unemployment rates, and poverty were starkly different between white and Black or Hispanic populations within the region. As a cumulative indicator, life expectancy across Greater Washington varies dramatically—in some cases dropping 30 years over a distance of fewer than 10 miles (see our last report for a map).

These and other disparities, which long predated the COVID-19 pandemic, were only widened by the events of the last 15 months—a common consequence of economic recessions and natural disasters. At this point, the fact that not all households were impacted equally is well documented. Analyses of the 2020 Census Household Pulse Surveys and other independent studies have revealed the disproportionate burden of the pandemic on lower-income Americans and people of color across numerous dimensions, including health, unemployment, and food insecurity.

Looking closely at these disparities within the Greater Washington region, as displayed in the map below, it is evident that the same lower-income communities were hit by wave after wave of impact.

Pandemic Impacts on Food Insecurity

The pandemic’s impacts on the economy have been well established. With the closure of businesses and organizations, unemployment spiked in the initial days of lockdowns in early spring of 2020, bringing swift and acute financial hardship to thousands of people across our region.

Over time, those numbers have gradually trended downward as businesses have adapted and restrictions have eased. However, despite steady declines following the dramatic increase seen in April of 2020, regional unemployment rates continue to hover at twice their pre-pandemic levels, meaning that far more individuals and families in our region continue to live without the income they maintained prior to COVID-19.

These impacts have been especially notable for those who were making lower incomes before the pandemic. Those individuals—many of whom worked in industries most quickly and severely affected by lockdowns—were the first and hardest hit by the economic impacts of COVID-19, and have also seen the most sustained downturn in employment rates.

Based upon the dramatic uptick in individuals seeking emergency food in our region during the pandemic—which has ranged from 30% up to as much as 400% at the organizations the food bank serves—unemployment has clearly had an impact on food security in the region. Directly correlating these trends, however, is complex.

During the pandemic, Feeding America released multiple estimates of possible food insecurity increases ranging from 20% to 60% that used projected rates of unemployment and poverty. Subsequently, however, several rounds of stimulus bills were passed to buffer the economic impacts the pandemic had on the country, altering the assumptions in those models and making it difficult to quantify the size of the food insecure population with certainty.

For these and other reasons, the Capital Area Food Bank has consistently looked directly to voices in the community, including our clients and partner nonprofits, to understand the size and nature of the need for support over the last 15 months. From regular check-ins and data-sharing with our partner agencies to a direct survey of nearly 2,000 of our clients, the results of which are featured in the following section, the Capital Area Food Bank’s access to real-time, ground-level insights has driven our strategy for responding to—and rebuilding from—the pandemic.

Ground-Level Insights About Food Insecurity

The Capital Area Food Bank centers its work on the voices of the people it serves. Accordingly, the organization has made a practice of conducting in-depth surveys with its clients on a regular basis. The COVID-19 pandemic offered an even greater reason to seek a clear understanding of the challenges that individuals experiencing food insecurity are currently facing, prompting the food bank to conduct a nearly 2,000-person study in the spring of 2021. The study recruited a broad cross-section of participants from CAFB’s food distribution sites and incorporated a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods.

While some findings from the survey were expected, others were surprising. The insights presented by the data raise new questions about the driving forces behind trends in who is experiencing food insecurity, their challenges and barriers to food access, and strategies for how best to help individuals move forward.

Insights About the Newly Food Insecure

One of the most surprising results of the quantitative survey was the number of respondents who had only become food insecure since the start of the pandemic. Two-thirds of respondents said they visited a food pantry for the first time in the last 12 months, with nearly 90% of those respondents saying their need for free food was a direct result of COVID-19.

While this should not be construed to suggest two-thirds of the food insecure population in the region is new to food insecurity, it does raise several questions about this population. Who are they, and how are they different from those who were food insecure before the pandemic? What were the common drivers that thrust them into food insecurity? Most importantly, what is needed to curtail their experience of instability, and what are the implications of their permanent addition to the food insecure population?

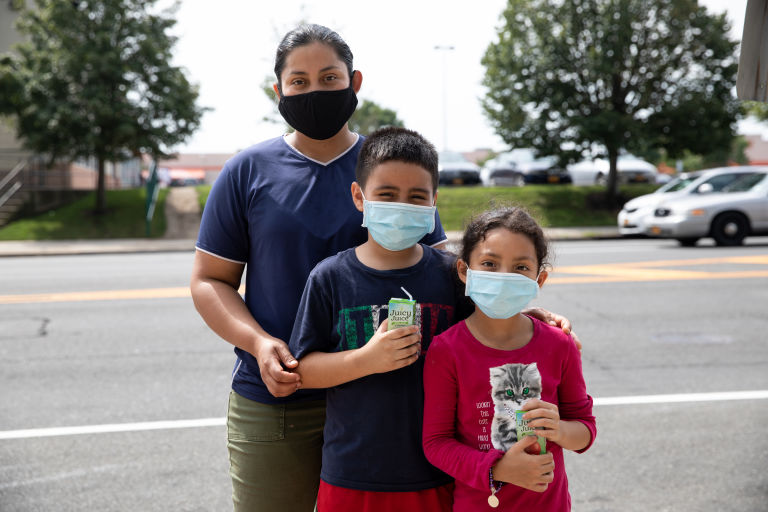

Across several socioeconomic dimensions, those who are newly food insecure are markedly different from those who were experiencing food insecurity before the pandemic. Those newer to food insecurity are more likely to be Hispanic, employed, to live in larger households with more children, to fall into more severe levels of food insecurity, and to be facing eviction. They are less likely to have a fluent English speaker in the household, know of more than one place to access free food, and understand the process of applying for government benefits.

The overrepresentation of Hispanic respondents among the newly food insecure can be explained in part by the concentration of Latino laborers in industries that were hit particularly hard by the pandemic. Nationally, Hispanic workers are overrepresented in the population unemployed because of COVID-19, a trend reflected in the food bank’s survey. Latino respondents reported higher rates of lost full-time employment and reduced hours at work due to the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, considering those data, Hispanic respondents also reported the highest levels of food insecurity and housing instability.

The newly food insecure population is also far less likely to be receiving benefits from the public sector. More than a year into the pandemic, enrollment rates for those new to food insecurity are still a fraction of those for individuals who were food insecure before last year. Results of the survey suggest that even programs that were targeted to those most affected by the pandemic, including Economic Impact Payments, Pandemic EBT, and unemployment insurance, did not benefit the newly food insecure as much as it did those who were already food insecure. When asked why, those newer to food insecurity were more likely to say they did not believe they were eligible or did not understand the process for applying.

I don’t think anyone expected this pandemic to last a full year.

Looking at these above data points in concert, the implications are clear: The newly food insecure population appears to be facing more severe levels of instability with fewer supports compared to those who were food insecure before the pandemic. While many of these disparities are concerning, it is especially important to note the larger household size and number of children in this group. Given the lifelong impacts that even short stints of poverty can have on children, the consequences of prolonged uncertainty are significant, both for these households and for the entire region.

Insights about Greatest Barriers to Food Security

Given the Capital Area Food Bank’s emphasis on addressing the root causes of food insecurity, an understanding of its clients’ self-perceived barriers to sustainability was a key area of focus for the survey. The picture painted by clients centered on the contrast between the cost of living in the region and low available opportunities to earn a living wage. This is particularly pronounced in Greater Washington, where the estimated annual cost of living for an average family of four—$110,000—is the sixth highest in the country. At the same time, more than half of local families earn less than that amount.

With regard to expenses, the number one self-reported barrier to food security for respondents was the cost of housing, one of the least surprising findings of the study. The economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have only exacerbated this issue. Of those who rent their residence (6 in 10 respondents), 30% are currently worried about being evicted, and 21% owe money in back-rent.

I just don’t know how to stretch it. I do the best I can.

In the case of income, the data make clear that despite a strong drive to earn a living, most clients are struggling to find jobs that can help them make ends meet. Nearly 60% of adults represented in the survey are currently employed, with another 16% looking for employment.

Almost 40% of respondents said that better job opportunities are their perceived solution to food insecurity. Perhaps consequentially, an additional 24% of respondents report that debt and a lack of savings or retirement are an impediment to their food security. These findings, particularly those revealing a desire for better employment opportunities, point to the need for regional investment in workforce development, vocational education, and opportunities for growth in the workplace.

Insights on Accessing Available Support

One noteworthy trend in the data was the low level of engagement with public benefits and social services, particularly among the most vulnerable people. About two-thirds of respondents screened as having “low” or “very low” food security, meaning they were likely cutting the size of meals or skipping meals because there was not enough money for food. For these respondents, engagement with public and social services is particularly low.

Only 23% of local households that the USDA would classify as food insecure are receiving SNAP, and 15% are receiving free and reduced-price school meals. These numbers shift from state to state in the region, with DC households reporting the highest rates of SNAP enrollment. Nearly 1 in 5 households surveyed is not receiving any government benefits at all. When asked why not, the top replies included not believing themselves to be eligible (61%); not being aware of these programs (17%); and not understanding the process for applying (10%).

A closer look at government benefits utilization patterns based on respondents’ race and ethnicity revealed additional insights. When reviewing enrollment rates for government programs aimed broadly at supporting lower income households, clear patterns emerge showing higher rates of utilization in Black and white households compared to Asian and Hispanic households. One potential reason for this trend is the higher percentage of immigrants in Asian and Hispanic households, who may either not qualify for these programs or experience barriers of risk, low trust, or low awareness with government agencies. When considering the fast rates of growth among Asian and Latino populations in our region, these trends of low utilization strongly suggest prioritizing support and outreach to these groups.

For programs that are targeted to households with children, there was greater parity among respondents. One exception to this pattern is the relatively high rate of enrollment in WIC among Latino respondents. These trends can be explained in part by the fact that nutrition assistance programs such as WIC and the National School Lunch Program (and, by automatic extension, Pandemic-EBT) are the only government benefits accessible to undocumented immigrants, aside from emergency Medicaid.

Aside from government benefits, respondents’ awareness of community-based resources to help them access food was very low. More than half of respondents would not know of another location to go for help if their free food distribution site closed. This number is even higher for households with children (65%), those with very low food security (70%) and households with no fluent English speakers (76%). These data suggest that despite a significant effort on the part of relief organizations across the region to support their food insecure neighbors, awareness of more than one source of free food remains low among those who may need it most.

It’s like a second job to figure out this stuff.

The low levels of engagement for government benefits and nonprofit services have numerous possible causes: language and literacy barriers, social stigma, the time- and opportunity-costs of applying for programs, fear of sharing personal information, and a general lack of confidence that the support received will be worth the work required.

In addition, transportation and mobility form an additional significant pair of barriers to accessing programs and services. Even excluding those who are homebound because of COVID-19, nearly half of respondents stated that transportation or mobility are a barrier to accessing food at least somewhat often. Respondents cite the lack of a personal vehicle and the price or inefficiency of existing transportation options as their top reasons for perceiving mobility as a barrier. This points to the number of food deserts within the region, particularly east of the Anacostia River.

The Capital Area Food Bank has found great value in these data for informing our work and strategy. We have also seen the powerful ways in which collaboration and information sharing can create positive outcomes at scale for our neighbors. We have published a cross-section of the results from the 2021 survey in an appendix to this report for the benefit of those who are interested in engaging with this research more deeply.

Creating Food Security & Economic Opportunity

With vaccines going into more arms each day and restrictions easing in our region and beyond, there is much to be hopeful about. Yet for those most financially impacted by the events of the last year, recovery—if it comes at all—will be many months or even years off, due to ongoing joblessness and significant debt stemming from permanent shifts in our economy.

In this environment, the deep disparities that existed before the pandemic risk becoming even more pronounced. Simply reaching the first rung on a ladder toward economic stability can be nearly impossible for someone struggling to put food on the table each day, a position where more people than ever currently find themselves.

The true challenge before us now is to seize this moment, as we recover from an unprecedented global event, to rebuild from the pandemic in ways that prevent inequities from worsening and expand opportunities for more people.

The remainder of this report outlines several strategies and recommendations for achieving this—in partnership with the public, private, and nonprofit sectors—by removing barriers to food access and enabling individuals and families to pursue economic advancement.

The link between food security and a thriving economy: The role that food can play in creating greater opportunity for our neighbors and greater prosperity for our region as a whole is foundational—though not always obvious.

An adequate nutritious diet enables, among many things, physical and mental health, learning, and concentration. All of these can contribute to an individual’s economic advancement over the course of a lifetime.

Food insecurity, by contrast, undermines each of these things. The negative health impacts of inadequate nutrition on people of all ages are well documented. Children who experience food insecurity are far less likely to perform well in school and to attain higher education. And food insecurity can impede the ability of adults to achieve and maintain employment, particularly in well-paying jobs. All this negatively affects economic opportunity and mobility.

While this is a problem at the individual level, it also creates negative repercussions for the whole regional economy by undermining the workforce and keeping low wage earners from increasing their spending power. But the reverse is also true: Economic growth that is distributed fairly across society increases economic participation in ways that lead to shared prosperity. In socioeconomic terms, this is known as “inclusive growth.”

There are broad economic upsides to fostering inclusive growth. Research shows that metro areas with more economic mobility also grow at higher rates. When prosperity and opportunity are not limited to the top few, metro economies grow faster, stronger, and for longer periods of time because they can tap into deeper veins of talent and draw from a more diverse, resilient, skilled workforce. Metro area initiatives around the world (including Greater Washington’s REDS initiative led by Connected DMV) are directly incorporating inclusive, equitable growth into their goals, just as corporations and nonprofits of all sizes use their positions to work toward the same aims.

Accordingly, the following subsections outline several strategies and recommendations, spanning all sectors, that can help to contribute to a more dynamic and inclusive regional economy for all.

The Public Sector: Creating Scalable Solutions through Policy

Governments at every level have an essential role to play in reducing inequities and increasing access to resources for those who need them. This role is especially critical when downturns and crises expose pre-existing weaknesses in social support systems. But even outside of those situations, the greatest opportunities for addressing barriers to food security and opportunity at scale can often only be realized through policy solutions.

In response to the challenges presented by COVID-19 over the last year, federal, state, and local governments quickly mobilized unprecedented resources. The expansion of SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) benefits—formerly food stamps—as well as the creation of P-EBT (Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer) and CFAP (Coronavirus Food Assistance Program) all helped to provide essential nutritional support to those who are facing increased food insecurity.

Unemployment insurance was revised to replace a higher percentage of worker wages, and eligibility was expanded to part-time and gig economy workers who are not traditionally eligible for protection. The Earned Income Tax and Child Tax Credits were expanded to reduce child poverty by nearly 50 percent.

For many households, recent program reforms offer support that just barely meet their pre-pandemic needs. As these new and expanded benefits begin to wind down, more permanent program reforms are necessary to create an adequate and equitable social safety net.

One of the most important paths for providing this support is through the modernization of the SNAP program. Although SNAP serves as a lifeline for beneficiaries, the methodology used to determine benefit amounts (the Thrifty Food Plan) is based on assumptions formulated in the late 1970s that no longer hold true for the needs of modern consumers or households.

Policy analysts estimate that nearly half of all households participating in the program still struggle with food insecurity. Updating the basis for benefit allocations to a modernized framework known as the Low-Cost Food Plan would increase SNAP benefits by an average of 30 percent, providing significantly greater support at the levels needed by our clients.

As previously mentioned, the results of the Capital Area Food Bank’s recent client survey make clear that those benefits are not being used by many people who qualify because they are unaware that the support exists, do not believe themselves to be eligible, or do not understand how to apply. Based on census data from the Capital Area Food Bank’s service area, an estimated 65% of eligible individuals are enrolled in SNAP. This translates to $260M in unclaimed food for our communities every year, and even greater lost opportunities due to hunger.

State and local governments can play a particular role in addressing these gaps by supporting government-or community-led utilization commissions tasked with understanding how many eligible individuals are currently using available programs and with enhancing program awareness, enrollment, and administration. To be most effective, these commissions should be composed of program participants, advocates, administrators, and policymakers focused on identifying tactical solutions for programmatic under-performance. The establishment of such commissions is one of many recommendations in the food bank’s comprehensive policy agenda for addressing food insecurity in the Greater Washington region.

Beyond policy solutions to modernize the social safety net, there are numerous opportunities to foster greater economic resiliency among our clients.

Enabling Long-term Wealth Accumulation: In response to the food bank’s recent survey, 1 in 4 of its clients disclosed they are struggling with debt and/or have no savings, and about 1 in 5 respondents is behind in rent or mortgage payments. These statistics signal a much broader challenge related to long-term wealth accumulation among food insecure communities. As noted earlier in the report, the racial disparities in homeownership and household wealth in Greater Washington are acute. Numerous policy solutions could help shrink these gaps, including creating public banking options through the United States Postal Service; increasing Social Security retirement benefits; shifting market dependency off employer-sponsored pension plans; and investing in generational home ownership for low-income communities and communities of color.

Enabling a More Stable Workforce: As noted earlier in the report, better employment opportunities emerged as a key to food security for many clients. Despite reporting higher rates of employment than the US average, most households represented in the survey are struggling with food insecurity, suggesting that their options for employment are not sufficient to help them reach sustainability. For many, this is because the job options available to them do not offer enough support to stay employed during normal life events, such as the birth of a child or an illness. Policymakers have several effective ways to address this, including guaranteeing paid sick, family, and parental leave, increasing targeted subsidized childcare and ensuring adequate health care coverage.

The Private Sector: Creating Opportunity through Employment and Workforce Development

Human capital is one of the most essential resources for any business to remain viable and to grow, making the ongoing availability of a strong labor pool critical to the success of companies across all industries. And corporate leaders throughout our region have indicated that they struggle to find the workers with the skills they need to achieve bottom-line results. Thus, food insecurity’s negative effects on education and employment opportunities poses a problem not just for individuals, but for businesses as well.

74% of food bank clients are working or actively trying to find work.

The connection between food insecurity and employment is clear and significant, both in existing data and the results of our client survey. Among food bank clients surveyed, 58% are working in some capacity and yet are food insecure; another 16% are unemployed and struggling to find a job.

Food insecurity and low-quality employment often coexist in a negative feedback loop: Low wages and insufficient resources available for food and other necessities perpetuate low economic mobility. Employment, therefore, plays a critical role in reducing barriers to food security and in creating greater opportunity.

The private sector has unique power—and a business imperative—to help break this negative feedback loop by expanding economic opportunities for the lowest earners in the workforce. Businesses can do this in multiple ways, and at many stages in the employment cycle:

Provide on-ramps for entering the workforce. Getting a steady job is a critical first step towards an individual’s ability to improve their financial stability. Yet paths to employment are not readily available for many members of our community. Businesses can create these paths by partnering with and investing in organizations that are helping to cultivate talent pipelines in communities that have traditionally had low access to high-quality employment opportunities. These can include organizations that connect high school students with career experience; community colleges; or skill development institutes aimed at adult learners who want to expand their skills.

Offer flexibility and benefits that enable individuals to remain in the workforce. While gaining employment is important for building economic opportunity, staying employed is just as essential. As addressed earlier in this report, there are many barriers that can keep people from remaining in a job, including illness, the need to care for a child or an older adult, illness, and other life events. While the public sector can play a significant role at the policy level, private sector businesses can independently provide benefits and enact policies—adequate leave and health care coverage, flexible time when possible—that support their employees’ ability to remain in the workforce.

Create pathways to advance and become part of a stronger talent pipeline. Opportunities for advancement at work can play a significant role in enabling greater financial security for individuals and their families. Initiatives that foster upward mobility can also help companies reduce turnover and grow their internal talent pool. There are many ways for businesses to enable this growth, including the creation of programs that help workers develop new skills or grow existing ones, connect employees with mentorship opportunities, and provide continuing education.

These kinds of workforce-building activities give rise to proven financial benefits. Such initiatives—many of which are being piloted in the Greater Washington metro area—also pose substantial opportunities for addressing racial and socioeconomic disparities by creating on-ramps for economic participation among a wider group of people. Experts have documented dozens of best practices in this arena.

While there is much the business sector can do on its own, the nonprofit sector can also play a role in strengthening our regional workforce and strengthening employment prospects for individuals. The Capital Area Food Bank, for instance, is partnering with skill development institutes and community colleges to help adult learners. These strategies provide food in a variety of formats to individuals enrolled in academic or skill development programs, with the goal of driving key outcomes such as attendance, retention, graduation, and employment. By using food both as a form of interim support and a commitment incentive, we are helping students achieve their goals and reverse the feedback loop between food insecurity and employment.

The Social Sector: Integrating Resources to Increase Impact

As the results of our recent study highlight, navigating the world of both public and nonprofit resources can be burdensome. Clients cited awareness of resources and benefits, transportation constraints, and English-language skills as barriers to engagement with social services. The time needed to find and engage multiple, separate forms of support presents a substantial additional hurdle. And clients must contend with each of these barriers every time they access a social service.

Barriers to prosperity are not singular for most people; they are numerous and interrelated, and they need to be addressed in tandem for interventions to be effective. Although many actors in the nonprofit sector are beginning to acknowledge this, many others offer singular services or interventions: a wellness screening, a training program, a childcare voucher, a financial advising appointment. Each of these holds potential for impact, but that impact can extend much further when providers address multiple issues at once.

Accordingly, an increasing number of nonprofits are integrating multiple forms of simultaneous support to make services more efficient to access, and to create synergy between those services. This approach requires individual actors in the social sector to view themselves as connectors, ensuring that their clients’ needs do not go unmet when there is support available—even if that support comes from another part of the network. By doing so, social service providers can maximize their impacts and create continuity of care that transcends service lines and life stages, allowing clients to transition toward greater stability and sustainability.

At the most basic level, this can be achieved through simple co-location of services—that is, placing multiple resources in one location—which removes the barriers of time and transportation needed to engage each one. Another effective approach for driving awareness and engagement of multiple services is closed-loop referral systems, a practice that starts with identifying a range of client needs and then connects different service providers around those needs through data-sharing. The fullest form of service integration blends two or more different supports at the same point of service delivery. This last approach can be highly effective at magnifying positive outcomes for clients, especially when root challenges are interrelated.

Many of the Capital Area Food Bank’s pilot programs are built upon one or more of these models. In partnership with health care providers, for example, the food bank is testing the theory that combining clinical care with increased access to healthy food amplifies positive results. By establishing food pharmacies in hospitals, issuing referrals to community food pantries from clinics, and providing free groceries at maternal wellness visits, the Capital Area Food Bank is recognizing food access as a driver of health outcomes.

The food bank is not alone in testing integration of multiple services. Many social service agencies are expanding their supports through partnerships with others or augmentation of their own programming. Medical practitioners, for instance, are increasingly acknowledging the benefits of integrating social services with health care. Skill development organizations are also more frequently expanding their programs to include financial advising, transportation stipends, and childcare.

Although the social sector is starting to move in this direction, further acceleration is needed. Nonprofit organizations would do well by their clients to extend themselves in partnership with others for the greater benefit of those they serve.

Conclusion

Well over a year on, COVID-19 has continued to expose and magnify the often-profound inequities that exist in our country and region. During the pandemic, these inequities have contributed to significant negative impacts on the health, economic stability, and food security of people who were already vulnerable. In the longer term, current trends show that they also threaten to drive even more individuals into a new cycle of economic hardship and food insecurity that could last for generations.

Our region now has a unique window of opportunity to change this trajectory. As we rebuild from the pandemic, each sector can take steps that will not only prevent inequities from growing worse, but also create new pathways to financial stability and food security for a far greater number of our neighbors.

While the past fifteen months have presented unprecedented challenges for people across the globe, they have also generated countless examples of what can be accomplished when individuals and communities work together to address them. In a moment when the imperative for change is clear, the potential to create it has also never been greater.